I don’t need to quote statistics on opioid misuse disorder to set the tone for this article. That’s a good thing I guess; it must mean our overall awareness of the topic is current. When I first started talking about this topic at conferences, about 70% of my presentation would be on the statistics regarding controlled prescription drug misuse and the definitions of tolerance, dependence and addiction, with a smaller section of the talk on actions we can take to mitigate opioid use disorder.

Now when I give a talk the portions of time spent on these two sections are pretty much flip-flopped. In addition during the statistics section, I try to gear the information provided specific to the locale of the group to whom I am speaking, so they can compare where they stand with the nation overall.

I also regularly share a synopsis of the CDC Guidelines for Opioid Prescribing during these conversations. These guidelines have been integral in supplementing and objectifying the CompAlliance Opioid Protocols we have had in place for the past five years. Recently I have begun to read about concerns voiced as to if we have swung the pendulum too far the other way, based on these guidelines? The concern is that people who truly need the medications will be denied access. This is always a valid concern. Our human nature tends to react this way on a regular basis when we perceive we have gone too far away from our original good intention. For regardless of the opioid manufacturing industry’s intentions, the healthcare providers initial intent was to manage the pain of their patients in a humane manner.

On June 19, 2018, the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control’s Board of Scientific Counselors (BSC), which is a federal advisory committee, will convene to hear about the CDC’s planned work to estimate best practice opioid prescribing in the US. This work is meant to address some key questions around opioid prescribing to help curtail the current opioid overdose epidemic in our nation. For instance, this work will answer questions such as: “What would the opioid prescribing rate be in the United States if best practices were followed?” And: “How much should prescribing change to bring prescribing rates in line with best practices?”

Date: The BSC meeting will be held June 19, 2018, 8:30 a.m. – 5:15 p.m., EDT and June 20, 2018, 8:30 a.m. – 12:15 p.m., EDT.

Discussion of this project and the establishment of the workgroup will be from 10:05 – 11:10 a.m., EDT on June 19th. Public comment on the workgroup will take place from 11:10 am – 11:40 am, EDT on June 19, 2018. The BSC will vote on the formation of the workgroup immediately following the public comment period. I plan to listen in on this workgroup and will report my understanding of the proceedings.

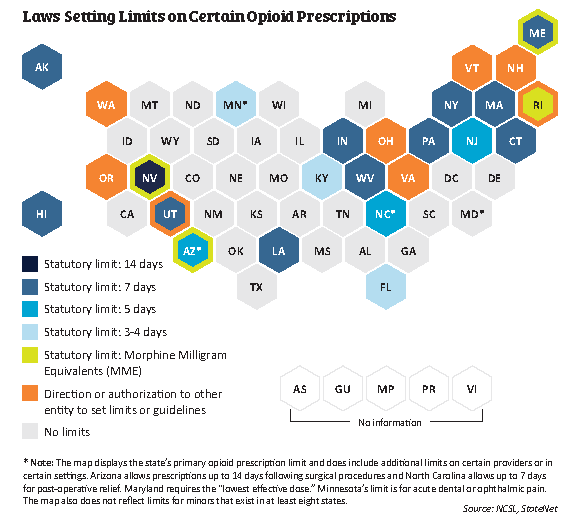

In the meantime, I decided to research a current legislative snapshot re: opioid prescribing to hopefully unearth some of the answers to this question. I found some information current as of April 2018 on the National Conference of State Legislatures website that I wanted to share.

“Legislation limiting opioid prescriptions debuted early in 2016, with Massachusetts passing the first law in the nation. Among other provisions in the comprehensive act, the state set a seven-day supply limit for initial (first-time) opioid prescriptions. Prior to the Massachusetts’ law, some states had passed bills related to prescribing, such as Washington’s legislation directing five professional boards and commissions to adopt rules related to chronic, non-cancer pain management, but none had set such a short time limit in statute.

By the end of 2016, seven states had passed legislation limiting opioid prescriptions, and the trend continued in 2017. More than 30 states considered at least 130 bills related to opioid prescribing in 2016 and 2017. According to NCSL’s tracking, 28 states had enacted legislation with some type of limit, guidance or requirement related to opioid prescribing by early April 2018.”

This site continues to describe what the legislation limits – mostly first-time opioid prescriptions to a certain number of day supply (seven days is most common, but there is variation – see the picture at the top of this article for more detail.) Many of the states specify these limits apply to treating acute pain, and most states set exceptions for chronic pain.

Most laws also allow exceptions for cancer, palliative care, treatment of SUD or MAT, or for the professional judgement of the provider prescribing the opioid. Many laws stipulate the exceptions need to be documented in the patient record. For the full synopsis of the states with actual links to their legislation, there is a very comprehensive table.

I do believe after reviewing this table, there are a few states where there is no exception for chronic pain, and we do need to address this and provide for an avenue to provide appropriate medication regimens for chronic pain.

If I were to have the say in how a state’s opioid protocols would look here are my suggestions for the out-patient setting:

- Day limitation – I believe either the 5 or 7 day limit provides enough pain medication after an acute injury. In many cases 3 days would be appropriate, and in my world, the physician would have read the best practices for pain management for the specific condition for which he is providing pain management, and would prescribe less as appropriate.

- MME Limit – The physician would prescribe within a 50 MME/day limit in this initial prescription.

- Evidence based non-pharmacologic and non-opioid pain management techniques would be provided along with this initial prescription with encouragement to utilize these techniques prior to or in conjunction with taking the opioid medication.

- Instructions on safe handling, usage, and disposal would be required. Alternatives to opioid pain management would be discussed and the patient would then make an informed decision as to whether any opioids would be prescribed through a shared decision-making process.

- Use of the state Prescription Monitoring Program would be mandated for both the physician prescribing and pharmacist dispensing (and all the PDMPs would be interconnected across state lines).

- For chronic pain exemptions or more complex injuries in which the physician believes more than the state limit of opioids is required, documentation in the patient file would include the approaches and methods that were attempted to manage the pain from a non-pharmacologic and non-opioid approach, the results of attempts to minimize and/or discontinue the opioid medications, the current activity level and quality of life that is achieved using the opioid medications. The current activity level and quality of life would be documented along with the pain level at each assessment. If these do not continue to improve or remain stable, then a plan for weaning should then be implemented.

- Mandatory controlled prescription drug education as a component of re-licensure for physicians, all professional nurses, and pharmacists. Also include training on Evidence-based approaches to managing pain without the use of opioids.

- Creating clear guidelines for any opioids prescribed for a minor for acute pain, including orthopedic injuries, dental, or ENT procedures. These prescriptions should be carefully monitored and only approved if evidence based guidelines demonstrate this is the only alternative for pain management for the condition. The evidence points to most of these type of injuries or procedures can be managed extremely effectively with non-pharmacological or non-opioid alternatives. The FDA Pediatric Advisory Committee will make recommendations regarding a framework for pediatric opioid labeling.

To facilitate these recommendations for opioid protocols:

- Provide physician reimbursement for the time and effort that safe and effective pain management requires.

- Continue to research evidence based approaches to non-pharmacologic and non-opioid pain management.

- Provide parity of benefit reimbursement for these approaches vs. just a medication approach to pain.