In my December 13, 2019, article on Switzerland’s Approach to the Opioid Epidemic, I detailed the history of the Swiss opioid epidemic and the “Four-Fold” Approach they used to address their epidemic. While the Swiss stressed prevention, they also allowed for a controversial (in the US) Heroin Substitution Program in their approach. As there are no one size fits all methods to address this epidemic, I decided I would share my research into Portugal, another country who has become renowned for their approach to addressing the opioid misuse epidemic to lend an additional perspective.

Forty years of authoritarian rule under the regime established by António Salazar in 1933 had suppressed education, weakened institutions and lowered the school-leaving age, in a strategy intended to keep the population docile. The country was closed to the outside world; people missed out on the experimentation and mind-expanding culture of the 1960s. When the regime ended abruptly in a military coup in 1974, Portugal was suddenly opened to new markets and influences. Under the old regime, Coca-Cola was banned and owning a cigarette lighter required a license. When marijuana and then heroin began flooding in, the country was utterly unprepared.

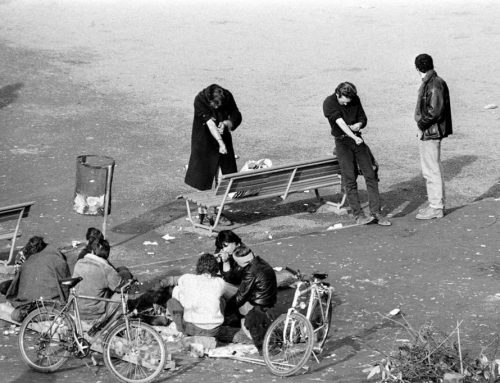

The crisis began in the south region of Portugal. The 80s were a prosperous time in Olhão, a fishing town 31 miles west of the Spanish border. Coastal waters filled fishermen’s nets from the Gulf of Cádiz to Morocco, tourism was growing, and currency flowed throughout the southern Algarve region. But by the end of the decade, heroin began washing up on Olhão’s shores. Overnight, Pereira’s beloved slice of the Algarve coast became one of the drug capitals of Europe: one in every 100 Portuguese was battling a problematic heroin addiction at that time, but the number was even higher in the south. Headlines in the local press raised the alarm about overdose deaths and rising crime. The rate of HIV infection in Portugal became the highest in the European Union. Lisbon became known as the heroin capital of Europe.

In 1977, psychiatrist Eduino Lopes pioneered a methadone program. He was the first doctor in continental Europe to experiment with substitution therapy, flying in the methadone powder from Boston. His efforts met with a public backlash, who considered methadone nothing more than state-sponsored drug addiction. In Lisbon, Odette Ferreira, a pharmacist, started an unofficial needle exchange program. She received death threats from drug dealers, and legal threats from politicians. She then bullied the Portuguese Association of Pharmacies into running the country’s, and the world’s first, national needle-exchange program. The first public drug treatment center did not begin operating until 1987; it employed an abstinence-based approach.

In the 1990s, Portugal faced a staggering opioid crisis. Roughly 1 in 10 individuals was using heroin; 1 percent of the population was addicted. Portugal’s prisons overflowed with those convicted of drug-related crime. High-risk behaviors produced public health crises, exploding HIV and hepatitis infection rates, homelessness and violent crime.

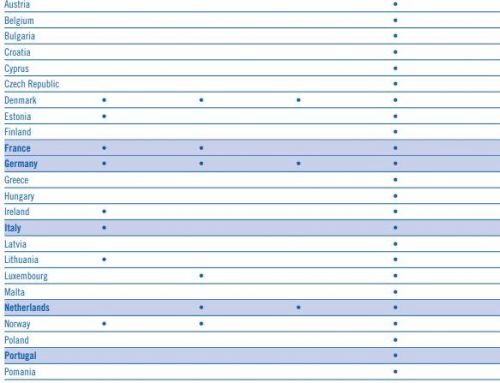

But thanks to an innovative law that went into effect in 2001, Portugal turned its crisis around. Portugal became the first country to decriminalize the possession and consumption of all illicit substances. Rather than being arrested, those caught with a personal supply (of up to 10 days) might be given a warning, a small fine, or told to appear before a local “Dissuasion Commission” – a doctor, a lawyer and a social worker with expertise in drug addiction – and were provided information about treatment, harm reduction, and the support services that were available to them. Dealers still go to jail.

The commission assesses whether the individual is addicted and suggests treatment as needed. Nonaddicted individuals may receive a warning or a fine. However, the commission can decide to suspend enforcement of these penalties for six months if the individual agrees to get help—an information session, motivational interview or brief intervention—targeted to his or her pattern of drug use. If that happens and the person doesn’t appear before the commission again during the six-month period, the case is closed. This shift to a public health vs a criminal approach is the so-called “Portugal Model”.

The opioid crisis soon stabilized, and the ensuing years saw dramatic drops in problematic drug use, HIV and hepatitis infection rates, overdose deaths, drug-related crime and incarceration rates. HIV infection plummeted from an all-time high in 2000 of 104.2 new cases per million to 4.2 cases per million in 2015. The data behind these changes has been studied and cited as evidence by harm-reduction movements around the globe. It’s misleading, however, to credit these positive results entirely to a change in law.

Portugal’s remarkable recovery, and the fact that it has held steady through several changes in government – including conservative leaders who would have preferred to return to the US-style war on drugs – could not have happened without an enormous cultural shift, and a change in how the country viewed drugs, addiction – and itself. In many ways, the law was merely a reflection of transformations that were already happening in clinics, in pharmacies and around kitchen tables across the country. The official policy of decriminalization made it far easier for a broad range of services (health, psychiatry, employment, housing etc.) that had been struggling to pool their resources and expertise, to work together more effectively to serve their communities.

“The language began to shift also. Those who had been referred to as drogados (junkies) – became known more broadly, more sympathetically, and more accurately, as ‘people who use drugs’ or ‘people with an addiction disorder’.”

This, too, was crucial. Portugal now has the lowest drug-related death rate in Western Europe, with a mortality rate a tenth of Britain’s and a fiftieth of the US.

It is important to note that Portugal stabilized its opioid crisis, but it didn’t make it disappear. While drug-related death, incarceration and infection rates plummeted, the country still had to deal with the health complications of long-term problematic drug use. Diseases including hepatitis C, cirrhosis and liver cancer are a burden on a health system that is still struggling to recover from recession and cutbacks. In this way, Portugal’s story serves as a warning of challenges yet to come as we in the US begin to look for treatment options for our citizens who are long-term misusers of drugs.

Though internationally there have been enthusiastic reactions to Portugal’s success, local advocates are frustrated by what they see as stagnation and inaction since decriminalization. They want to establish supervised injection sites and drug consumption facilities, make naloxone more readily available, and implement needle exchange programs in prisons.

Mobile Methadone Clinic

For those who aren’t ready or are unwilling to seek treatment, the emphasis currently is on harm reduction. They bring care to the streets – including psychologists, nurses, doctor and social workers. They provide psychological support, exchange syringes, hand out condoms and urge drug users and other vulnerable populations to take advantage of shelters, hospitals and treatment centers. The patients they serve are encouraged to go at their own pace. The main goal is to build a relationship with the user. They believe without the relationship; they can’t do anything.

Currently Portugal has a drug policy detailed in three strategic documents: The National Strategy for the Fight Against Drugs 1999, the National Plan for the Reduction of Addictive Behaviors and Dependencies 2013-20 and Portugal’s Action Plan Horizon 2020. Portugal set up a central agency to coordinate its response nationwide. Every health district in the country has an outreach team that visit addicts every day and gets to know their stories and needs.

The New York Times reports that Portugal spends less than $10 per citizen per year on its drug policy. Meanwhile the US has spent some $10,000 per household over the decades on our drug policy.

“Yet let’s also be realistic about what is possible: Portugal’s approach works better than America’s, but nothing succeeds as well as we might hope.”

I have reported on the “Deaths of Despair” – deaths by suicide, drug and alcohol poisoning, alcoholic liver disease and cirrhosis in the US in previous blog articles. Over the past 3 decades, deaths of despair were most prevalent in areas with high unemployment, and extremely high opioid prescribing.

There is concern that for all the success, budget cuts are threatening the future of Portugal’s addiction treatment system. Europe’s financial crisis in 2009 took a heavy toll on the country. As unemployment went up, so did alcoholism and addiction. As part of the austerity measures that followed, the government eliminated the central agency responsible for coordinating the country’s drug treatment program. Among the other casualties was a program that placed recovering addicts in job training. It is feared the country may begin to see an increase in addiction due to increased risk factors and decreased support by the government.

Can we in the United States seriously consider decriminalization as one of the alternatives to turn our opioid crisis around? Would we as a country agree to a uniform central agency coordination of our national drug treatment program? Would we consider mobile methadone clinics, particularly when considering only until very recently most drug treatment in the US centered around abstinence as the first treatment alternative, and MAT only when abstinence failed?