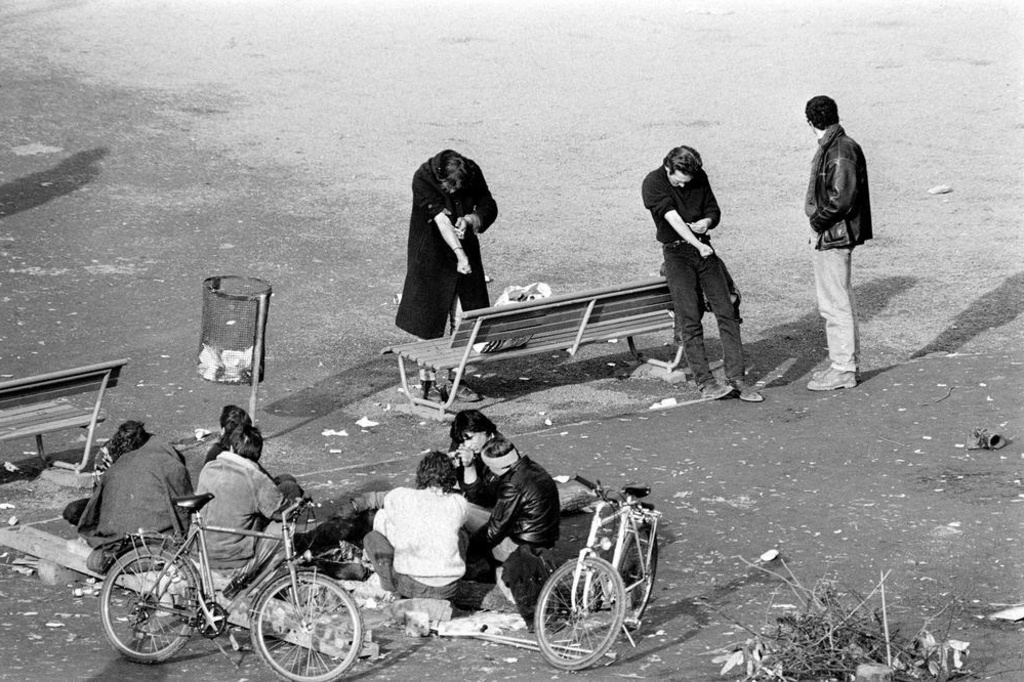

(View of Platz Park during the Open Drug Scene)

If you had asked me 5 years ago what we needed to do to help one of our patients to stop misusing opioids, I most likely would have said the best approach is cold turkey, or a quick taper with total abstinence from that point forward. I am learning this may not be the best or most effective approach. Switzerland took a very different approach to the opioid epidemic in their country. Much of what I will be sharing may be uncomfortable for an American audience.

I read an article in the North Carolina Health News where they describe a park with the nickname of “Needle Park”. Beginning in the 1980’s the park began to be used by up to 3000 heroin users and dealers daily, many of whom were infected with HIV. This park was in downtown Zurich and was part of Switzerland’s “open drug” scene. Heroin users could freely inject the drug without being arrested. As some witnesses from the time described, drug users were lying in their own bodily fluids, while others were shooting up next to them. Rats were everywhere, and the park reeked of decay.

Addicts and dealers flooded in from across Europe, until authorities shut the park down in 1992. Many people desperately needed urgent medical care daily. Doctors volunteered their time, at first against the will of the authorities, to treat drug users with infected, weeping wounds or for overdoses, and to hand out clean needles. The authorities then allowed the doctors to work in this way in the park.

However, the authorities later gave into heavy political pressure and police were sent in leading to chaotic scenes of addicts being forced to flee, without any alternative to turn to. No organized social support had been set up in its place. “Needle Park” closed for good on February 5, 1992. A heavy gate was put in place across the entrance to the park. It did not solve the problem, as the addicts then began congregating in different areas across the city.

Switzerland implemented a harm reduction program and reduced the spread of HIV within the drug scene, and from drug users into other population groups, earlier than many countries. Each canton (US equivalent of a state) developed strategies based on its drug problem. By 1985 it was obvious that ‘needle sharing’ was the most significant pathway in the transmission of HIV.

Thilo Beck, chief of psychiatry at Arud Centers for Addiction Medicine said, “The pressure to find a solution became overwhelming. All options had failed. Politicians, the business community and members of civil society were forced to sit together and work together in order to find an answer.”

The policy of policing and prevention had not worked. The Swiss are a conservative people, and they decided to adopt a pragmatic approach. A new approach emphasized therapy and treatment, efforts that previously had been overlooked. Instead of criminalizing addicts, new policies aimed to reintegrate them back into society.

In 1992 Zurich made methadone available to heroin users who were formerly denied the treatment. Addicts who got therapy also found housing with a social project. “Those programs helped tremendously to get people off the street,” one of the addicts who were helped during this time stated.

Just two years later, Zurich became the first place in the world where therapy programs handed out heroin prescriptions to heavy and long-term opiate users for whom other substitutes wouldn’t work. In 1993 and 1994, two popular initiatives were presented, with opposite objectives.

The initiative entitled “Youth without Drugs” called for a strict, abstinence-oriented drug policy that contains elements of repression, prevention, and therapy. It sought to prohibit medical prescription of narcotics (heroin, opium, cocaine, cannabis, and hallucinogens) as well as of similar substances.

The initiative presented in 1994, entitled “For a Reasonable Drug Policy” (“Droleg”), proposed the opposite, namely, the decriminalization of drug use, cultivation of plants used to produce drugs, and legal possession and purchase of drugs for personal use. Further, it suggested that the state supervise cultivation, import, and production of narcotics and, thereby, make trade in narcotics for non-medical purposes possible within a defined legal framework providing protection of youths and a ban on advertising. Both alternatives were found to be too extreme by the Federal Government and Parliament and were ultimately rejected.

By 1995 many of the new policies showed success. The support system for drug addicts started to work; police, social and medical services increasingly cooperated. Eventually, Zurich police shut down the last remaining drug camp in the heart of the city.

In 1996, experts made recommendations including decriminalization of drug use as well as medical prescription of heroin as a new therapy, provided that the positive results seen up to then are scientifically confirmed. They created a “Four-Fold” Approach” of Swiss drug policy including this heroin-assisted therapy;

- to reinforce the role of the federal government regarding coordination and quality control,

- to abolish prosecution of the purchase, possession and consumption of cannabis,

- to permit discretion in allowing, planting, growing, production and trade in small quantities of cannabis and

- to permit discretion in allowing the purchase, possession and consumption of illicit drugs other than cannabis.

In a public vote in 1997, the usually conservative Swiss public rejected the adoption of stricter drug policies, legitimizing the new, less punitive approach. In 2008 they finally voted to put the strategies developed in the 1990s into law based on the principles of a ‘four pillar system’: repression, prevention, harm reduction, and treatment. These days, new heroin addicts are rare in Switzerland, while other countries, including the US are witnessing a devastating heroin comeback.

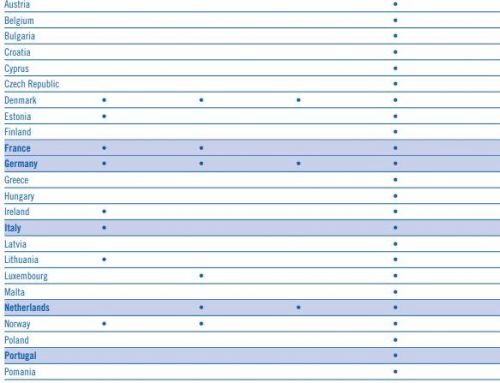

Services like the methadone and heroin substitution programs are still active today. Almost 70% of the heroin addicts are in substitution therapy, the highest ratio in the world. Most receive methadone, but 8% receive heroin. Globally handing out heroin as a treatment drug remain controversial. Few other European countries have followed its example. Interestingly, Iran and China, have copied its methadone substitution program. The Swiss trials of HAT prompted five other studies, and now there are HAT programs in Denmark, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, the UK and Canada.

To qualify for HAT, the patient must have had at least two years of opioid dependence and tried and failed two other addiction treatments and be at least 18 years old. Providing medical grade heroin, in the Swiss’ opinion frees up the time spent finding the street product, enabling users to focus on things like housing, family and employment. Of note, Dr. Beck states 80% of the people receiving HAT are over 44 years old, and he believes if they had started this program earlier, they would not have the heavily impaired people they are still treating.

Family doctors now prescribe about 60% of opiate substitution treatment in Switzerland and the Internet was vital in informing users about access to treatment, according to Dr. Ambros Uchtenhagen. Drug overdose deaths dropped by 64%, HIV infections dropped by 84%. Home thefts dropped by 98%. And the Swiss prosecute 75% fewer opioid-related drug cases each year. The European Monitoring Centre determined HAT programs result in significant savings to society, particularly in the reduction of costs from criminal justice proceedings and incarceration of drug users.

In the IMPROVE study Dr. Thilo Beck evaluated the current results of the Swiss OMT Model. I see some parallels with concerns we have in the US.

- 31% of the physicians providing OMT who responded to his study are over age 60

- A significant number of the physicians providing OMT were not aware of the current Swiss guidelines for OMT, including the existence of effective treatments other than methadone, and the importance of diversification to optimize and individualize therapy to the needs of the patient

- They find there is a lack of physicians willing to provide OMT; this was attributed to lack of education, and financial barriers to physician compensation

- They need to increase access for patients to OMT, and increase the attractiveness of treating opioid-dependent patients to physicians

- Liquid methadone remained the most common OMT medication preferred by patients and prescribed by physicians in Switzerland

- The number of buprenorphine patients remains low, though their studies show it is equally effective and is easier to administer as doses can be sent home, once the patient is stabilized

(Current View of Platz Park)

Prevention is the first pillar of the Swiss program.

“It should be pointed out that the most notable change in prevention has been a transition from the concept that prevention was a matter of preventing someone from ever trying drugs to today’s concept of preventing the health and social problems related to drug use, thereby integrating the person’s social network and environment as well.”

This is one of the concepts that may be uncomfortable for us as Americans to absorb. One of the objectives of the Swiss strategy is to focus not only on drugs but also on personal resources and the strengthening of the individual’s social network. As someone who has experienced the societal problems associated with drug addiction within their close family, I believe this is an area we need to address in the US. I believe our beginning to focus on the Social Determinants of Health is a good first start.

The third pillar – Harm Reduction. The purpose of this pillar was to reduce the health and social risks and consequences of addiction. These include needle exchanges, injection sites, offers of employment and housing, support for women who prostitute themselves to buy drugs, and consultation services for the children of drug-addicted parents. Drug addicts have access to such programs without having to meet any prerequisites.

“The objective of these harm reduction services is to limit as much as possible the negative consequences of addiction so that the addict resumes a normal existence. In addition, these measures are aimed at safeguarding and even increasing the addict’s chances of breaking the drug habit.”

Despite Switzerland’s seemingly progressive approach to OMT, the system is far from perfect, according to Dr. Beck’s IMPROVE study. Treatment barriers and unmet needs identified by the IMPROVE study include political, financial and social problems. These present opportunities for improvement.

What are some of the takeaways that can translate to our workers’ compensation patients? I am convinced we as an industry need to focus on three different groups of recovering workers – the opioid naïve patient (how do we prevent inappropriate opioid prescribing), the patient who has been on opioids for less than 6 months (this time frame could be shorter) and is appearing to have difficulty transitioning to other methods of pain relief, and our long-term opioid prescribed patients. The methods to address the needs of each of these groups varies.

- How do we educate all case managers, claims professionals, prescribing physicians, nurse practitioners and physician assistants to prevent inappropriate prescribing of opioids?

- How do we communicate the non-opioid and non-pharmacological alternatives available to prevent inappropriate opioid prescribing or to ease a transition off opioids?

- How do we support our long-term opioid prescribed patients in a way that they do not feel judged, but have the support to explore treatment options that could assist them to reduce or eliminate the use of opioids?

- What if we are unable to successfully eliminate the opioid medication?

- How do we educate and support a larger cohort of prescribers to begin to provide MAT in the US?

- What social services need to be included?

Resources for this article:

Switzerland Fights Heroin with Heroin, January 28, 2019 by Taylor Knopf, North Carolina Health News

Swiss Drug Policy should serve as model: experts, October 25, 2010, Stephanie Negehay, Reuter News

Besson, Jacques & Beck, Thilo & Wiesbeck, Gerhard & Haemmig, Robert & Kuntz, André & Abid, Sami & Stohler, Rudolf. (2014). Opioid maintenance therapy in Switzerland: An overview of the Swiss IMPROVE study. Swiss medical weekly. 144. w13933. 10.4414/smw.2014.13933.

How and Why AIDS changed drug policy in Switzerland J Public Health Policy. 2012 Aug;33(3):317-24. doi: 10.1057/jphp.2012.20.

The US can learn a lot from Zurich about how to fight its heroin crisis, February 12, 2016, Stefanie Knoll, Global Post, PRI

Social Determinants of Health, HealthyPeople.gov