Recently, I met two podiatrists that practice in New York and perform workers’ compensation IMEs along with their usual practice. They were down to visit one of my friends and play some golf in Florida. When they found out I worked in the workers’ compensation industry, they verbalized frustration about some of the more challenging patients that are referred for IMEs. The physicians discussed how these patients seem to have few coping skills, minor injuries impact them in a way that would be easy to overcome for most patients, and they seem unable to adhere to treatment plans.

In my early days as a case manager I mirrored the ideas and thoughts these two physicians shared during our conversation. When referred a Recovering Worker (RW) with this type of presentation, I tended to get frustrated with the non-adherence and seeming lack of cooperation on their part. I would wonder if this RW was a “malingerer”.

However, as my experience and research has developed over the years my thoughts on adherence in the RW population has modified. I attempted to share with these two physicians some of the research I have performed on Adverse Childhood Experiences, the Social Determinants of Health, and their impact on adherence. I could tell they were skeptical, but they did listen politely. It was “off the cuff” and I know I probably didn’t do a very good job, but I hope it at least got them to think of potential reasons for the behavior of some of the RWs they encounter, and how they might positively impact the situation in the future.

Following this conversation, I read a wonderful article in my (Case Management Society of America) CMSAtoday magazine, Issue 1, 2020 on “Trauma-Informed Care and Social Determinants of Health in the Healthcare Setting: A Path Toward Stability”. I wish I had read this article prior to our conversation, as I believe the information in this article would have helped me to more clearly speak on the causes and methods to address a RW who seems overwhelmed by an injury, is unable to adhere to their plan of treatment and appears to have little resources or capability to do so.

Consider a RW who works at a minimum wage job, uses the bus for transportation, or relies on rides from family if she can get them. This worker may have several children at home, little or no support system, and misses work at times for family or other unknown reasons. This RW has comorbidities of obesity, is a smoker and a diabetic. The RW did not complete High School and does not have a GED. She has had a previous work-related injury which took longer than expected for resolution. How many of your RWs have at least some of these risk factors?

As a case manager, we perform a comprehensive Initial Evaluation to identify the potential psychosocial factors that may influence and impact the physical condition during the treatment and rehabilitation phases of the work injury. In the article Trauma-Informed Care, it is “advocated for a strong understanding of the social determinants of health and how these, coupled with chronic exposure to trauma, can dramatically alter an individual’s experience with the healthcare system, and moreover all aspects of life.”

The Social Determinants of Health

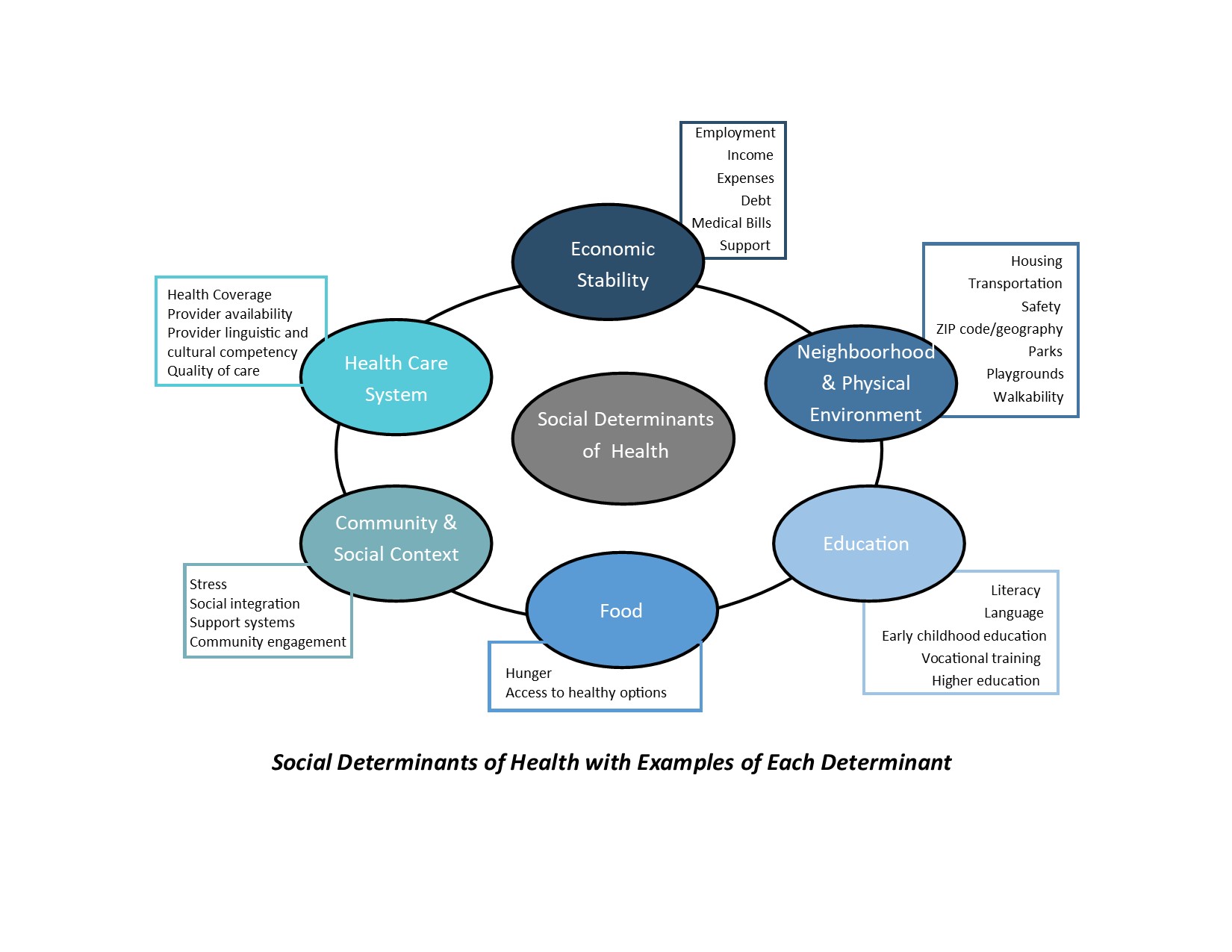

A wonderful resource on the social determinants of health (SDoH) is the Healthy People 2020 (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion) which acknowledges interrelatedness of health and a variety of social drivers. As I have shared in previous articles, the WHO defines SDoH as “conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age,” and systems shaping the conditions of daily life.

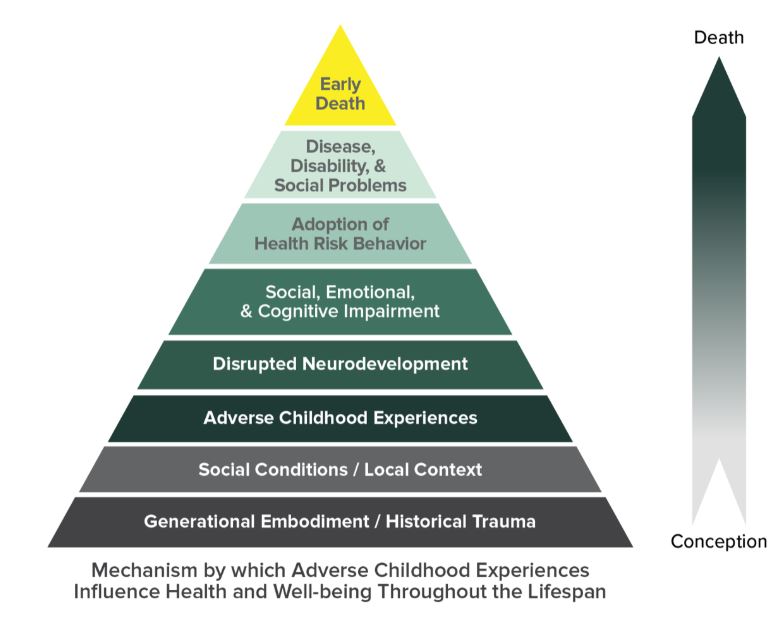

The study: “Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults; The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study” performed by Kaiser Permanente and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Felitti et al., 1998) further demonstrated a connection between psychosocial factors and medical wellness does exist. Below are some of their findings on the health implications of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) detailed in the CMSA article:

- People with 6+ ACEs die nearly 20 years earlier than those with an ACE score of 0

- Headaches occur 2x more with ACE score > 5

- COPD occurs 2.6x more with ACE score > 5

- Risk of ischemic heart disease is 3.5x higher with ACE score of 7+

- Risk for rheumatic diseases increases 100% in individuals with > 2 ACEs

- Hepatitis occurs 2.5x more with ACE score > 4

- Adult alcohol use increases 2 – 4x with ACE score > 1

- Prescription drug misuse increases 40% with ACE score > 5

- Depression occurs 4.5x more with ACE score > 4

- Suicidality occurs 12x more with ACE score > 4

- 50% of patients who suffer physical injuries resulting from interpersonal violence have experienced ACEs

Facing these SDoH and ACEs can create chronic stress within individuals. Stress can be healthy and can help us to grow and change when it occurs within healthy relationships. In the study, “Stress begets stress: the association of adverse childhood experiences with psychological distress in the presence of adult life stress”1. The study found “A significant direct association exists between ACEs and psychological distress. Adult life stress seems to be a mediator of this relationship. Interventions targeted at psychological distress should address both early life adversity and contemporary stress.”

“Simply put, what influences each person’s overall medical wellness is driven by far more than just our genetic makeup, our diagnoses, and the medications we take; a multitude of psychosocial drivers play into that equation as well.”2

What does this mean for us in the workers’ compensation industry? As we grow in our desire in the workers’ compensation industry to learn and understand about ACEs and SDoHs, we also need to integrate a trauma-informed care model into our case management practice.

“Trauma-informed care offers…a strengths-based framework that is grounded in an understanding of and responsiveness to the impact of trauma, that emphasizes physical, psychological and emotional safety for both providers and survivors, and that creates opportunities for survivors to rebuild a sense of control and empowerment. As we view each individual through a trauma-informed lens, approaching with empathy rather than judgement or defense can change the intervention, or even just the delivery of the intervention, to create a more positive experience for everyone involved.”2

Trauma-Informed Care was a new concept to me prior to reading this article. The author suggests trauma-informed care doesn’t give us more work to do, but rather new tools to do the work we as case managers are already committed to perform. One suggestion was rather asking “what’s wrong with you?”, ask, “what happened to you?” or “how can we help?’. It is easy to view a patient like those I described in my initial example as non-adherent, difficult, disengaged or even unworthy of help; by taking a trauma-informed approach, we can realize that many of the reasons the individual is struggling with adherence are systemic and beyond his or her control.

When we assess for the SDoH through a trauma informed lens, we can begin to offer solutions to the issues most responsible for lack of adherence in our Recovering Workers. We should begin by identifying which social determinants are the most pressing for our patients. The CDC has information and downloads re: Social Vulnerability. There is a fact sheet and maps of the US and counties showing overall social vulnerability. In the “ACE Study” they call for “further research and training to help medical and public health practitioners to understand how social, emotional and medical problems are linked throughout the lifespan.” Increased awareness may lead to improvements in health promotion and disease prevention programs. I look forward to performing more research on trauma-informed care.

1Manyema M, Norris SA, Richter LM. Stress begets stress: the association of adverse childhood experiences with psychological distress in the presence of adult life stress. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):835. Published 2018 Jul 5. doi:10.1186/s12889-018-5767-0

2Trauma-Informed Care and Social Determinants of Health in the Healthcare Setting: A Path Toward Stability, KIMBERLY BROWNE, LCSW, ACM-SW, CMSAtoday, Issue 1, 2020