In Part 1 of this series I touched on the ANA Position Statement providing ethical guidance and support to nurses and some of the responsibilities a nurse has when managing a patient in pain.

I was asked after publishing Part 1 why a Case Manager would be responsible for assisting in the management of pain, to describe some of the non-pharmacologic pain management techniques a case manager could recommend and detail their effectiveness.

In Part 2 we reviewed why a Case Manager is responsible for assisting in the management of pain. We concluded though while we as case managers do not administer medications, our responsibilities as an RN and Case Manager do include: education, assessment, using evidence-based assessment tools, exploring non-pharmacologic options, communication, documentation, active adherence and participation, etc.

In Part 3 I will address the second part of the request above – describe some of the non-pharmacologic pain management techniques a case manager could recommend along with research into their effectiveness.

To start this type of research I like to use resources that do Systematic Reviews of multiple studies. Some of the resources I typically use are the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews – a journal and database for systematic reviews in health care, PubMed Central – a free full-text archive of biomedical and life sciences journal literature at the US National Institute of Health’s National Library of Medicine.

I also reviewed the US Department of Health and Human Services NIH National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health Pain Information for Health Professionals. Their overview states: Pain is the condition for which adults in the United States most often use complementary and integrative health approaches. This includes musculoskeletal pain (back pain, neck pain, joint pain, etc.), headache, and pain associated with specific conditions (e.g., arthritis). The scientific evidence to date suggests that some complementary health approaches may provide modest, short-term effects that may help individuals manage the day-to-day variations in their chronic pain symptoms. In most instances, though, the amount of evidence is too small to clearly show whether an approach is useful.

On this site are links to Clinical Practice Guidelines for a variety of chronic and acute pain related conditions.

For chronic pain in general:

- A 2017 review looked at complementary approaches with the opioid crisis in mind, to see which ones might be helpful for relieving chronic pain and reducing the need for opioid therapy to manage pain. There was evidence that acupuncture, yoga, relaxation techniques, tai chi, massage, and osteopathic or spinal manipulation may have some benefit for chronic pain, but only for acupuncture was there evidence that the technique could reduce a patient’s need for opioids.

- Research shows that hypnosis is moderately effective in managing chronic pain, when compared to usual medical care. However, the effectiveness of hypnosis can vary from one person to another.

- A 2017 review of studies of mindfulness meditation for chronic pain showed that it is associated with a small improvement in pain symptoms.

- Studies have shown that music can reduce self-reported pain and depression symptoms in people with chronic pain.

As case managers working with a recovering worker experiencing pain, some of the teaching moments could include:

- Don’t use an unproven product or practice to postpone seeing a health care provider about chronic pain or any other health problem.

- Learn about the product or practice you are considering, especially the scientific evidence on its safety and whether it works.

- Talk with the health care providers you see for chronic pain. Tell them about the product or practice you’re considering and ask any questions you may have. They may be able to advise you on its safety, use, and likely effectiveness.

- If the recovering worker is considering a practitioner-provided complementary health approach such as spinal manipulation, massage, or acupuncture, ask a trusted source (such as your health care provider). Find out about the training and experience of any practitioner you’re considering. Ask whether the practitioner has experience working with your pain condition.

- If the recovering worker is considering dietary supplements, keep in mind that they can cause health problems if not used correctly, and some may interact with prescription or nonprescription medications or other dietary supplements. 1Certain chronic conditions, several of which cause pain, may occur together;

Research on Mindfulness & Cognitive Behavioral Therapy on Chronic Pain

Following are examples of systematic reviews performed on some of the more popular complementary pain relief options discussed in the workers’ compensation arena today.

Chronic Pain and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: An Integrative Review

Thirty-five studies were included in this review. Results revealed that CBT reduced pain intensity in 43% of trials, the efficacy of online and in-person formats were comparable, and military veterans and individuals with cancer-related chronic pain were understudied.

Citation: Knoerl, R., Lavoie Smith, E. M., & Weisberg, J. (2016). Chronic Pain and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: An Integrative Review. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 38(5), 596–628. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945915615869

Comparative evaluation of group-based mindfulness-based stress reduction and cognitive behavioural therapy for the treatment and management of chronic pain: A systematic review and network meta-analysis.

This review compares mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) to cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) in its ability to improve physical functioning and reduce pain intensity and distress in patients with chronic pain (CP), when evaluated against control conditions.

CONCLUSIONS: This review suggests that MBSR offers another potentially helpful intervention for CP management. Additional research using consistent measures is required to guide decisions about providing CBT or MBSR.

Citation: Khoo EL1,2, Small R1,3, Cheng W1, Hatchard T4, Glynn B1, Rice DB1,5, Skidmore B6, Kenny S1,7, Hutton B1, Poulin PA1,8,9.

Yoga treatment for chronic non-specific low back pain.

AUTHORS’ CONCLUSIONS:

There is low- to moderate-certainty evidence that yoga compared to non-exercise controls results in small to moderate improvements in back-related function at three and six months. Yoga may also be slightly more effective for pain at three and six months, however the effect size did not meet predefined levels of minimum clinical importance. It is uncertain whether there is any difference between yoga and other exercise for back-related function or pain, or whether yoga added to exercise is more effective than exercise alone. Yoga is associated with more adverse events than non-exercise control but may have the same risk of adverse events as other back-focused exercise. Yoga is not associated with serious adverse events. There is a need for additional high-quality research to improve confidence in estimates of effect, to evaluate long-term outcomes, and to provide additional information on comparisons between yoga and other exercise for chronic non-specific low back pain.

Authors: Wieland LS1, Skoetz N2, Pilkington K3, Vempati R4, D’Adamo CR1, Berman BM1.

Scoping review of systematic reviews of complementary medicine for musculoskeletal and mental health conditions.

OBJECTIVE: To identify potentially effective complementary approaches for musculoskeletal (MSK)-mental health (MH) comorbidity, by synthesising evidence on effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and safety from systematic reviews (SRs).

CONCLUSIONS:

Only one SR studied MSK-MH comorbidity. Research priorities for complementary medicine for both MSK and MH (LBP, OA, depression, anxiety and sleep problems) are yoga, mindfulness and tai chi. Despite the large number of SRs and the prevalence of comorbidity, more high-quality, large randomised controlled trials in comorbid populations are needed.

Authors: Lorenc A1, Feder G1, MacPherson H2, Little P3, Mercer SW4, Sharp D1.

Summary

Currently most studies examined demonstrate some minimal benefit from the complementary treatment reviewed, however they also recommend more research is needed.

So, what can we recommend as Case Managers that is evidence based? Currently it seems there is good evidence for mindfulness and/or CBT as a complement to treatment when the biopsychosocial assessment suggests the recovering worker may benefit from these approaches. But what about the everyday basics that we all take for granted? During your initial assessment did you look at the recovering worker’s BMI, stress, sleep and exercise habits?

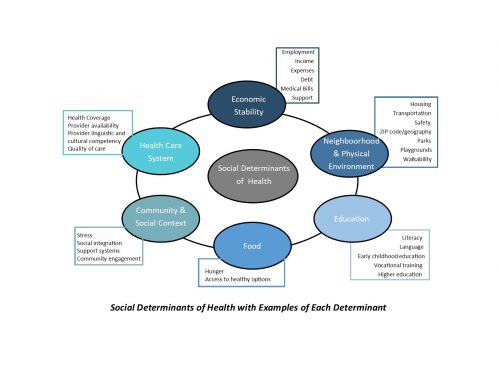

Case Managers can be very effective in teaching good sleep hygiene, addressing good nutritional habits, reinforcing any Home Exercise Program prescribed by the physician or physical therapist, and addressing some of the Social Determinants of Health that may be impacting the ability of the recovering worker to adhere to the prescribed treatment plan.

Contact us for more information about the CompAlliance approach to case management of pain in the recovering worker.