Focusing on functional improvement vs. “Healing the pain”

Traditionally when the injured worker reports pain, the first impulse is to “heal that pain”. It is just human nature isn’t it? When our kids fall, we kiss their “boo boos” don’t we? When our friends are hurting, our first impulse is to give them a hug.

In the realm of workers’ compensation and in pain management in general, the physician and the nurse case manager both want the injured worker to feel better, and as a result achieve increased functional capabilities. So how did we get to this place where opioids were part of the mix to achieve these goals?

Since the mid 1990s the standards for pain treatment have changed significantly, moving from historically undertreating pain to the perception of “no ceiling dose” in pain management. How did this change take place? Physicians were told by the producers of OxyContin that patients could not get addicted to narcotic analgesics if they were in pain. This is explained very chillingly in the video, “OxyContin Poster Children 15 Years Later“. Physicians were also told at that time that patients who develop physical dependence on opioids could be easily tapered off.

Purdu Pharma, the producer of OxyContin pled guilty to providing faulty research on these topics and paid $634M in fines. They are now actively involved in education on use of opiates, prescribing, etc.

I have read statistics that only a very small percentage of medical schools even address pain management during medical training. In addition, the physicians are under pressure to see more patients in order to achieve a profitable practice and support all the staff needed to coordinate services within their office and communicate with the complexities of all of their patients’ insurance plans.

As such, the physician’s ability to keep up-to-date with the best evidence based practices for pain management are limited. Please note, there are legitimate times when the injured worker sustains an objective orthopedic or neurological injury or immediately post-op when a short course of the lowest dose opioid that will address the acute pain, is appropriate.

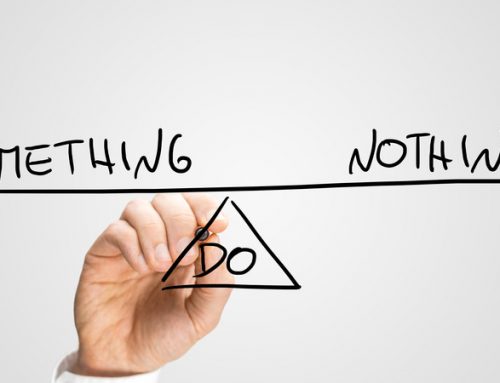

So how do we turn around this thought process to focus on functional capabilities vs. relief of pain? Changing the dialogue from focusing on pain to focusing on functional capabilities is key. At each meeting with the injured worker the case manager should be assessing the injured worker’s self-reported pain levels and interference with functional ability. At CompAlliance we utilize a Graded Chronic Pain Scale to assess pain levels and interference with functional levels. This assessment is integrated into the conversation with the treating physician and is documented in our reports to the claims professional.

The only reason to use an opioid is to increase function and tolerance of activities designed to restore previous capabilities [in PT, home exercise, etc.]. As such, the question on all stakeholder’s minds needs to be: “If the opioid is not assisting the injured worker to achieve these goals, and a temporarily increased dosage did not help either, then why does the injured worker remain on an opioid?”

Education as to best practices for non-opioid alternatives based on evidence based approaches is essential. The case manager should be prepared to discuss alternatives based on these approaches.

If you have an injured worker who is on opioids and is not reporting improved functional capability the above questions need to be addressed. A case manager who has been trained in opioid protocols, meeting face to face with both the physician and injured worker, is one of the first steps in addressing the ongoing appropriateness of the current treatment plan.